Sudan’s War Now: The Human Cost and Global Fallout

War in Sudan: A Deep-Dive Analytical Report (2025)

The ongoing conflict in Sudan is a profound humanitarian and geopolitical crisis, deeply rooted in historical, political, and socio-economic factors. The following report presents a comprehensive, in-depth analysis of the conflict, covering its origins, actors, humanitarian consequences, political dynamics, and future scenarios. Each section has been expanded to provide detailed explanations, rich context, and visual elements to enhance understanding.

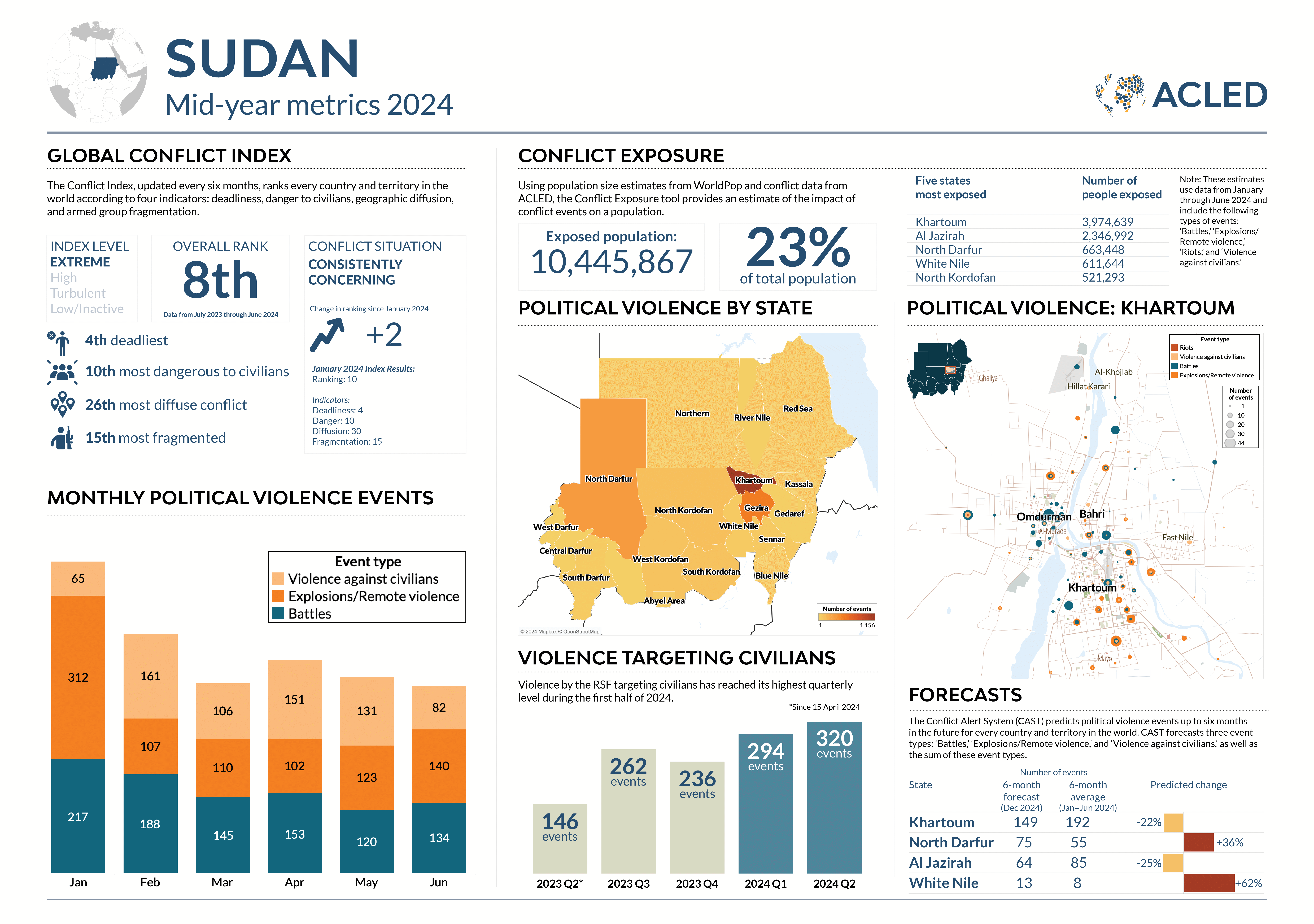

Infographic: Sudan Crisis Overview

1. Origins and Conflict Dynamics

1.1 Historical Background

The roots of Sudan's current conflict are intertwined with decades of political instability, authoritarian rule, and regional marginalization. After the overthrow of Omar al-Bashir in 2019, a fragile transition emerged, shared between the military and civilian representatives. However, deep-seated mistrust between military factions soon escalated into open confrontation.

On April 15, 2023, a decisive breakdown occurred between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), commanded by Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo. These two groups, once nominal allies under the transitional government, engaged in full-scale military conflict across major urban and rural centers, particularly Khartoum, Darfur, Kordofan, and eastern Sudan.

1.2 Key Actors and Power Structures

- Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF): The regular army, holding strategic military bases, political influence, and international recognition.

- Rapid Support Forces (RSF): Paramilitary units originally formed from Janjaweed militias, controlling gold mines, fuel depots, and key highways.

- Local Ethnic Militias: Numerous groups in Darfur and Kordofan maintain influence over regional territories, often exploiting the chaos for self-preservation.

- Regional and International Powers: Countries such as Egypt, UAE, and neighboring nations provide arms, funding, and political support to various factions, creating a proxy dimension to the war.

1.3 Geography of Conflict

The war’s geography is multi-layered. Khartoum sees urban warfare with shelling, drone strikes, and control over vital infrastructure such as airports and bridges. Darfur experiences mass displacement and ethnic targeting, while Kordofan becomes a logistical and strategic battlefield for both military and paramilitary forces. Eastern Sudan has recently witnessed drone attacks targeting fuel depots, signaling expansion into previously less-affected regions.

Map: Sudan Conflict Zones & Territorial Control

1.4 Recent Military Escalations

- Targeted drone strikes on civilian and logistical sites in eastern Sudan.

- Intense urban combat in Khartoum, including artillery shelling in neighborhoods and marketplaces.

- Sieges of towns such as Babanusa in West Kordofan, creating severe shortages of food, medicine, and water.

- Strategic targeting of bridges, airports, and communication centers to disrupt civilian life and logistics.

2. Humanitarian Crisis

2.1 Scale of Displacement

Over 13 million people have been displaced since the start of hostilities. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) reside in camps, makeshift shelters, or with host communities. Neighboring countries, including Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Libya, are hosting millions of Sudanese refugees, straining local resources and creating regional security concerns.

2.2 Food Insecurity

Food insecurity has reached alarming levels, particularly in North Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile. Humanitarian access is limited due to ongoing clashes. Millions are reliant on aid delivered by humanitarian organizations, yet convoys often face delays or attacks. Chronic malnutrition in children and pregnant women is rising, with famine warnings reported in isolated areas.

2.3 Civilians Under Threat

- Indiscriminate shelling of urban areas, markets, and hospitals, leading to high civilian casualties.

- Massacres targeting ethnic groups such as Masalit, Fur, and Zaghawa in Darfur, echoing patterns from previous conflicts.

- Sexual violence and exploitation, disproportionately affecting women and girls in camps and conflict zones.

- Disruption of education and livelihoods, contributing to long-term social instability.

- Physical destruction: Artillery strikes, air or drone attacks, and nearby fighting cause structural collapse or make facilities unsafe to operate.

- Occupation & looting: Armed units often occupy wards, remove equipment, or steal drugs and supplies; this both halts services and introduces violence into healing spaces.

- Power and water cuts: Destruction of local utilities — power substations, water pumps, sanitation systems — makes even intact clinics unable to sterilize instruments, run refrigeration for vaccines, or provide safe deliveries.

- Death, injury and flight: Doctors, nurses, midwives, and community health workers have been killed, injured, detained, or forced to flee their posts for safety.

- Staff shortages and skill gaps: The exodus of experienced clinicians leaves facilities staffed by junior or non-specialist staff, reducing the quality of care for complex cases.

- Psychological toll and burnout: Remaining staff face unbearable workloads, moral injury, and trauma, increasing errors and reducing capacity for sustained care.

- Cholera and acute watery diarrhoea: Water supply and sanitation breakdowns produce explosive cholera outbreaks, which kill rapidly without prompt rehydration and antibiotics.

- Malaria resurgence: Disruption of insecticide spraying, bednet distribution and antimalarial treatment increases transmission and severe disease, particularly among children.

- Measles outbreaks: Suspension of routine immunization leaves children vulnerable — measles spreads quickly in crowded shelters and has high mortality where nutrition is poor.

- Other infectious threats: Respiratory infections, tetanus (due to injuries), hepatitis, and vector-borne zoonoses all rise when health services and surveillance fail.

- Essential medicines: Antibiotics, antihypertensives, insulin, antiretrovirals and treatments for chronic diseases become intermittent or unavailable.

- Oxygen and consumables: Oxygen cylinders, concentrators, tubing and masks are in critical shortage; this is catastrophic for treating severe pneumonia, obstetric haemorrhage, trauma and COVID/respiratory patients.

- Surgical supplies and blood: Sterile kits, sutures, analgesics and safe blood stocks fall below minimal levels, turning otherwise survivable surgical emergencies into deaths.

- Maternal mortality: The collapse of obstetric services increases maternal deaths from haemorrhage, sepsis, obstructed labour and hypertensive disorders.

- Neonatal care gaps: With limited neonatal intensive care, premature and low birthweight babies face much higher mortality.

- Child malnutrition: Food insecurity and repeated infections produce acute and chronic malnutrition, stunting physical and cognitive development.

- Acute psychological distress: Survivors of attacks, witnesses of violence, and those who lost family members show high levels of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress.

- Children and adolescents: Young people exposed to violence display behavioural problems, learning difficulties and long-term cognitive impacts.

- Limited services: Mental health support is rarely prioritized during emergencies and is severely under-resourced in Sudan, leaving most people without psychosocial care.

- Lost childhoods: Years of poor nutrition and interrupted schooling damage lifetime earnings and societal productivity.

- Chronic disease burden: Uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes and infectious disease sequelae will raise the chronic care burden for decades.

- Reconstruction complexity: Rebuilding buildings is feasible; rebuilding trust, training professionals, and restoring routine immunization and chronic care systems takes a generation.

3. Health and Public Services Collapse

The protracted war in Sudan has not only destroyed buildings and supply chains — it has systematically dismantled the country’s ability to protect and preserve life. Health systems are both direct targets and collateral victims: hospitals and clinics have been shelled, looted, or occupied by armed groups; ambulances have been stopped or fired upon; and supply lines for medicines, oxygen, vaccines, and medical consumables have been severed. The results are catastrophic and multifaceted. Below we unpack, in expanded detail, the immediate failures, the cascading secondary effects, and the long-term generational consequences of this collapse.

3.1 Direct damage to health infrastructure

Hospitals, clinics, primary health centres, laboratories and blood banks have been damaged or rendered non-functional in multiple regions. Damage takes several forms:

Expanded explanation: a single referral hospital out of service does not merely remove one point of care — it removes an entire referral chain. Emergency patients who formerly would be stabilized and referred to that hospital now face longer transport times, overburdened neighbouring facilities, or no care at all. With critical care units offline, treatable conditions (severe infections, obstetric complications, trauma) become lethal. Laboratory closures also mean that disease surveillance collapses: outbreaks are recognized late, diagnostics are delayed, and public health responses lag behind transmission.

3.2 Health workforce depletion and protection risks

Medical personnel are suffering severe and compounding risks that undermine service delivery:

Expanded explanation: human capital is the most difficult part of any healthcare system to replace. Training a surgeon, a neonatal intensive care nurse, or a laboratory technician takes years — and wartime losses mean that even if infrastructure were rebuilt quickly, the skilled workforce might not return. In the interim, mortality from childbirth, neonatal conditions, trauma and complex infections is likely to rise sharply.

3.3 Cholera, malaria, measles and communicable disease outbreaks

The environmental and social conditions created by war — crowded, unsanitary camps; contaminated water supplies; interrupted vaccination programs; and reduced vector control — are perfect incubators for infectious disease. The main disease threats include:

Expanded explanation: beyond immediate case counts, infectious disease outbreaks perpetuate a vicious cycle. Cholera and diarrhoeal disease worsen malnutrition, which in turn increases susceptibility to measles and other infections. Malaria in pregnancy raises risks of stillbirth and low birthweight, with lifetime consequences for children’s growth, cognitive development and economic prospects. Without functioning surveillance, by the time authorities notice a spike in cases it is often too late for targeted interventions; mass campaigns are costlier and less effective when delayed.

3.4 Severe shortages: medicines, oxygen, surgical supplies

Wartime supply chain breakdowns cause acute shortages across essential commodities:

Expanded explanation: even if a surgical theatre remains physically intact and staffed by a surgeon, without sterile supplies and blood the risk of postoperative infection and peri-operative death increases dramatically. Chronic disease patients (diabetics, hypertensives, people living with HIV) face accelerated morbidity when their lifelong medicines are interrupted — leading to heart attacks, strokes, and preventable deaths that further erode community resilience.

3.5 Maternal, neonatal and child health impacts

Women and children bear a disproportionate share of the health burden in war:

Expanded explanation: maternal and child health losses are not only tragic but transmissible across generations: the death of a mother increases the child’s risk of death and abandonment, and malnutrition undermines schooling and future productivity. These losses compound to reduce the nation’s human capital for decades after the conflict ends.

3.6 Mental health and psychosocial consequences

Trauma, grief, chronic stress and the breakdown of social networks drive a parallel epidemic of mental health needs:

Expanded explanation: the invisibility of mental health means its effects are often underestimated. Untreated trauma increases suicide risk, domestic violence, substance misuse and community breakdown — all of which hinder recovery and reconciliation. Community-based psychosocial interventions (safe spaces, child-friendly activities, counseling) are low-cost, high-impact responses that are currently scarce in many affected areas.

3.7 Public health surveillance and disease control collapse

Effective public health requires functioning surveillance, labs, cold chains and reporting systems — all of which are heavily impaired. The consequences include late detection of epidemics, failure to contain outbreaks, and inability to monitor vaccination coverage or track displaced populations’ health needs.

Expanded explanation: without surveillance, humanitarian actors cannot prioritize resources efficiently. Donors may not realise the full scale of nutrition crises or epidemic spread until irreversible damage has occurred. Re-establishing surveillance — even basic community reporting — is a critical first step for any recovery plan.

3.8 Long-term generational consequences

The health system collapse will reverberate long after active hostilities cease:

Expanded explanation: international reconstruction that focuses only on bricks and mortar will fall short. Sustainable recovery requires long-term investments in workforce training, public health systems, supply chains, and community reconciliation. Without this, the cycle of vulnerability and disease can persist across generations, undermining peace dividends and economic recovery.

Immediate priorities (first 0–3 months): protect hospitals and ambulances, open humanitarian corridors for medicines and oxygen, deploy emergency mobile clinics, restart vaccination catch-up campaigns, supply rehydration and cholera kits, and provide mental-health first aid.

Medium term (3–18 months): reconstitute referral networks, rehabilitate damaged facilities, re-stock blood banks and surgical kits, re-train displaced health workers, and scale up community-based nutrition and maternal health programs.

Long term (18 months+): invest in medical education and retention, rebuild laboratory and surveillance capacity, modernize health information systems, strengthen primary health networks, and institutionalize protections for healthcare in national law and international agreements.

- Neighboring countries host large refugee populations, straining food, health, and security systems.

- Regional powers, including Egypt and UAE, are actively engaged in the conflict, supplying arms, strategic advice, and political support, potentially turning Sudan into a proxy battlefield.

- Global supply chains for gold and other resources are disrupted, affecting regional economies.

- Mistrust between SAF and RSF factions.

- Fragmented authority with multiple local militias controlling territories.

- Competing international interests hindering neutral mediation.

- Short-term risks: famine, disease outbreaks, civilian displacement, and urban devastation.

- Long-term risks: fragile or failed peace processes, state reconstruction challenges, social fractures, and potential resurgence of violence.

- Opportunities: sustained international engagement, humanitarian aid, political reconciliation, and eventual demilitarization of conflict zones.

4. Critical Conflict Events

4.1 El Fasher Massacre

Thousands of civilians, mainly from non-Arab ethnic communities, were killed during a wave of targeted violence in North Darfur. This tragic event has international implications, with calls for war crimes investigations.

4.2 Omdurman Market Attack

Artillery shelling on February 1, 2025, killed 56 civilians and wounded 158 others, destroying the main commercial hub in Omdurman and severely impacting the local economy.

4.3 Siege of Babanusa

A prolonged siege has left thousands trapped without access to food, water, or medical aid. Humanitarian organizations face serious logistical constraints reaching the town due to ongoing fighting.

4.4 Eastern Sudan Drone Campaign

RSF-led drone attacks have targeted airports, fuel depots, and infrastructure, reflecting a shift toward asymmetric warfare and signaling expansion of the conflict to previously quieter regions.

5. Regional and Geopolitical Implications

Sudan’s war is creating ripple effects across East and North Africa:

6. Political Landscape

Peace negotiations have repeatedly stalled due to:

Accountability for human rights violations is central to future political settlements. Rebuilding state institutions, ensuring civilian governance, and reconciling local communities will be essential post-conflict.

7. Risks and Future Scenarios

The situation remains highly fluid and dangerous:

8. Why It Matters

The Sudan war is more than a local conflict; it has profound implications for human rights, regional stability, and global humanitarian norms. Timely international response, accountability, and reconstruction plans are critical to prevent further human suffering and potential regional destabilization.

Conclusion

The war in Sudan is an acute humanitarian disaster and a complex geopolitical crisis. With millions displaced, critical infrastructure destroyed, and ethnic violence rampant, immediate and long-term international action is essential. The choices made by Sudanese leaders, regional actors, and the international community will shape the country’s survival, reconstruction, and peace trajectory for decades.

No comments

Share your opinion with us